THE EVOLUTION OF THE IMAGINATIVE ARTS

And why comic art IS a valid art form

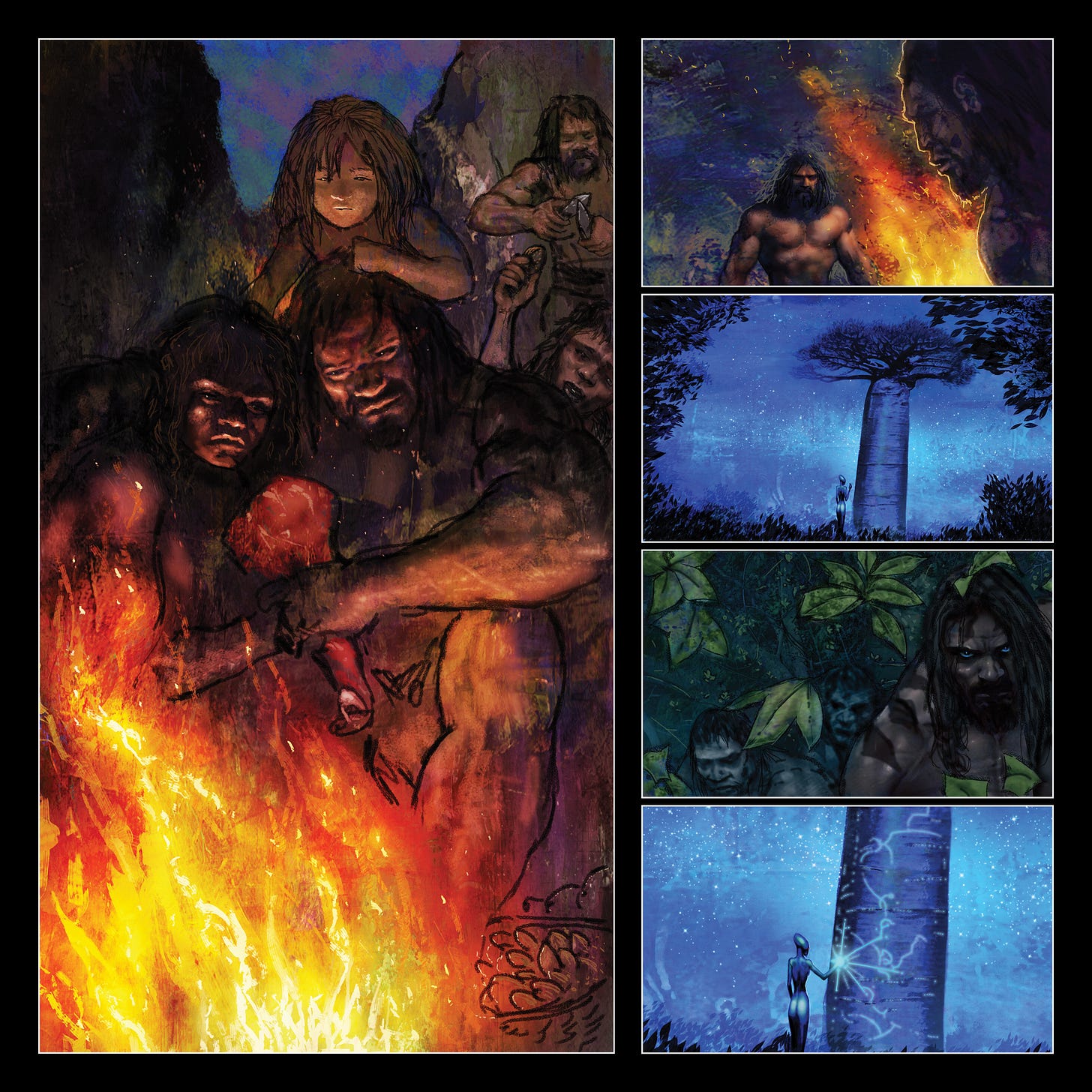

Longer ago than memory, a piece of wood, and the fire that burned it, did more than cook and smoke food, gift a nighttime cave with light and warmth. When the flame was out, and only a burned stump remained, somebody took that and they marked a wall with it.

With a few faltering lines they started to draw.

From those first drawings arose all the future written languages of our race. Symbols depicting objects were aligned with vocal utterances representing the same thing.

And there is a bigger human story that gets sidelined and is never fully gifted the historical and cultural significance it merits: Scrawling in charcoal they created mythic art, and its amazing legacy.

Perhaps the first piece of art you could claim as truly mythic comes in the form of ‘The Sorcerer’, from the Three Brothers cave in France – dated at approximately 13,000bc. It’s an anthropomorphic horned beast-man, or shaman, and the very first representation of something that doesn’t exist.

In literature, the most ancient poem we have is a Mesopotamian fantasy called The Epic of Gilgamesh, from 2500bc. Beyond that we get Homer's Iliad and Odyssey -The Trojan War, Achilles, Hector, Odysseus and his ten-year journey home. The great quest, the fellowship, the un-surmountable obstacles, and (of course) the monsters!

But what was Homer getting at? What purpose did these fantasies serve?

Well - The Romans give us their version of the story in Virgil's the ‘Aeneid’ – and here it’s pretty clear what the intention is: Propaganda. Aeneas, just a bit-part in the Iliad, is recreated as the fictional ancestor of Julius Caesar, and therefore of his adopted son Augustus Caesar. Aeneas also makes a great journey, out-witting and defeating any and all adversaries and eventually founding Rome. Virgil gives his fellow Roman’s something to swell their chests - He makes them mythic by dint of this faux history: They are all the children of Troy.

Germany later gives us Siegfried and the Dragon, the epic Ring Cycle.

Ireland gives us the hero Cuculain in The Tain - who had to be rolled in the snow to cool down after battle.

We Brits get King Arthur. Geoffrey of Monmouth writes the obscure prophecies of a magician called Myrddyn, from the Welsh, whom he renamed Merlin - in his book The History of the Kings of Britain.

Then there's our oldest written poem, an Anglo-Saxon tale concerning a certain Viking called Beowulf, and the beast, Grendel, who he literally disarms.

And to my eyes, at least, the work of Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel is an illustration of another epic mythology of man that serves a similar purpose.

The comparisons to be made are endless, but the point is clear: Mythic storytelling is one of the highest and most ancient of art-forms from which sprang ALL literature and ALL stories.

But still – what did, and what does, it do for us? Why is it important?

Well - what it did was confirm our struggle with nature, and help us understand our environment.

It empowered us, emboldened us before battle.

It gave us strength in times of famine or hardship.

It ennobled us - giving us heroic ancestors, whose parents were gods - thereby linking us directly with our creators.

As Isaac Asimov once observed: these were the parents we invented for ourselves, that would not grow old and die, but would instead remain perpetually bigger and better and stronger than we could ever be. And so this, in turn, also gifted us hope beyond life. It made death comprehendible and acceptable to us.

Mythic art is, therefore, aspirational and inspirational.

But what of cultural and social significance?

Swift's Guliver's Travels used that ancient magical quest format to create biting satire.

Lewis Carol's Alice in Wonderland seems to be a drug-fuelled quivering meditation on denial and frustrated longing - but wearing mythic clothing.

In art Goya, Brueghel and Bosch all used mythic imagery to supreme effect.

Later the surrealists would create works that trawled the imagination. Dali in particular created work that was anthropomorphic and mythic.

The imaginative bent of mankind, our ability to create fictions, does more than just swell our hearts - it gets us looking forward. It can comment on now – as allegory – or it can be prophetic. This same power of conception led early scientists to speculate on the nature of the universe.

Leonardo Da Vinci imagined submarines, helicopters and gliders.

H.G. Wells imagined time-travel.

Asimov envisaged AI.

Arthur C. Clarke predicted space-walks and moon-landings.

So it’s clear the tradition, at least, is honorable - rooted in our most ancient past, our primordial and archetypal selves.

(As an aside - I’ve noted that we tend not to gift much of our current art the same auspicious origin-out-of-fantasy. Given that we used to put our fears in the hands of the epic saga writers, and our hopes in the hands of visionaries, I find it sad that much of what we apparently consider ‘fine Art’ views the mythic with more than a little contempt.)

I read somewhere – I think it was an Alan Moore interview - that Jane Eyre ended the reign of the mythic arts, focusing the collective mind on social politics, the affairs of the day. But mythic art utilizes a unique human faculty – and it is that facility that steeled us to cross over continents and oceans, and eventually to travel to the moon and beyond.

We have written great stories in every medium – in charcoal and ocre on rock; in grooves gouged in the earth or sand; in carved relief on stone or wood; in twisted and beaten in metal; in scrawls of pigment on flesh or papyrus; in printed ink on paper, bound up into books.

I would argue that our ability to imagine the fantastic, the impossible, the mythic – as comics artists do - is one of the key things that defines us as human beings. We don’t have to listen to the artelligentia that think they can distinguish a pseud-grail of ‘fine’ capital ‘A’ Art from all other art.

All art is art - no matter how naïve - and it is all subjective.

Art from ‘Eden’s End’ by Grant Morrison and Liam Sharp

See Grant Morrison’s XANADUUN for more!

I’m reading all your posts and enjoying every word. When you mentioned Epic literature in this post, I thought of TESTAMENT, an epic series that I really enjoyed. Are you planning to share more in the future about the background and creative process of that series? It's one of my favorites, and I have all the issues. The way you so powerfully depict different planes of existence simultaneously on the same page is something I still really enjoy and often revisit.